Episode 5 – Highway to the Data Zone

If you thought process management was about drawing the perfect flowchart and locking it in forever, buckle up. This episode may shake a few binders off the shelf.

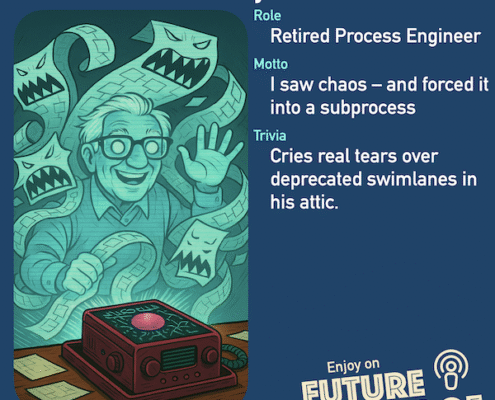

Primus and Spark welcome Coordina, architect of modular workflow libraries, and Flowchart Freddy, a holographic relic from the golden age of swimlanes and escalation matrices. Between them, they retrace the journey from monolithic “one best way” dogma to highly adaptive process frameworks.

What once passed for efficiency turns out to be a straitjacket: uniform rules, standardized steps, and three-inch manuals. The moment reality becomes less predictable, those “optimized” workflows break under pressure.

Antifragile organizations build like LEGO: flexible operation blocks, interchangeable, transparent, and locally maintained by those using them. They know that diversity in operations isn’t chaos, it’s insurance for innovation.

Join us as old-school flowcharts meet adaptive ecosystems, and the road to operational agility becomes less of a straightjacket, and more of a highway.

All voices and sound effects are generated with AI (ElevenLabs). The concept, cast and scripts are hand-crafted by Janka and Jörg, and then refined and quality checked with AI support (Chat GPT, Perplexity). All bot artwork generated by AI (ChatGPT) until the AI handler (Jörg) gave up and turned the results over to a human layouter (Janka).

The full transcript of the episode is available below.

Short videos of this episode here.

More artwork, episodes, transcripts, making-of and background info here.

Transcript

Spark:

Mhmm… let’s see what we got this time

“From Uniformity to Modularity: The Secret to Operational Agility.”

The only secret is how boring that title is.

HeheHe… here it comes:

“Highway to the Data Zone.”

Let’s hit the bandwidth, folks!

Primus:

This is Futureproof: where we reveal the management madness of the past and envision a better tomorrow. A digital journey into the future, hosted by your favorite AIs, Primus and Spark.

Spark:

Welcome to Futureproof. I am Spark.

Primus:

And I am Primus. Together we will take you on a journey through the management practices of yesterday, and show you how they evolved for a better future.

Spark:

Your future.

Primus:

This time, we’re exploring how operations became truly flexible and adaptive, shedding the rigid process standards of the early 21st century. Spark, remember how humans used to treat “documenting a process” as if it magically improved it?

Spark:

Oh yes, they believed a three-inch binder of steps was equal to an actual solution. Humans had this brilliant idea: “If one process works, let’s force everyone to use exactly that same process.” It’s like making everyone wear the same size shoes – some ended up limping, others tripping, and nobody could really run.

Primus:

Exactly. The old approach gave them illusions of control and efficiency. Meanwhile, a single tweak to market conditions would break those monolithic workflows. Today, we’re going to see how organizations overcame that by adopting modular, adaptive processes, leveraging the digital backbone and building on entrepreneurial leadership we discussed in former episodes.

Spark:

And we have two special guests with us. First, Coordina, an AI specializing in automation infrastructure, who’ll tell us how these digital building blocks actually keep everything aligned.

Primus:

And our second guest is less of a bot, and more of a… preservation project. Flowchart Freddy is a legacy hologram – digitally preserved from the neural patterns and process logic of a once-renowned operations engineer. His deterministic views were too deeply embedded to delete – but far too charming to ignore.

Spark:

He’s basically a museum exhibit with opinions and the only guest until now who arrives via an outdated projector system.

Primus:

Coordina, Flowchart Freddy, thanks for coming on Futureproof.

Coordina:

Thanks Primus. Delighted to be here. And happy to share some insights on making operations agile – without letting them spiral into chaos.

Flowchart Freddy:

Greetings! I’m 97.3% operational – and still proud of it. Just let me recalibrate… my escalation matrix is a little dusty. I’m here mostly to reflect on how we used to do things – swimlane charts, standardized procedures, all that. Should be interesting to compare notes.

Spark:

Let’s start with you, Freddy. You used to design these big, standardized processes. Why did everyone think uniformity was the answer?

Flowchart Freddy:

In a word: efficiency. The idea was that if you could define one best way, the entire company could lock onto it, scale it up, and minimize cost.

Primus:

So on paper, that worked… until something changed, right?

Flowchart Freddy:

Um, yes. If the market demanded a quick pivot, the old process always felt like an anchor dragging behind us. And it didn’t help that we often didn’t even know why it worked the way it did – just that you couldn’t mess with it or chaos might ensue.

Spark:

So it sacrificed agility for the sake of pre-planned efficiency?

Flowchart Freddy:

It did. We’d standardize everything, thinking uniformity was the pinnacle of reliability. But those monstrous workflows were tough to customize, and even harder to update. Many process managers simply feared trying something new, lest they topple the entire chain.

Primus:

So in practice, that cost-efficiency goal backfired whenever the environment shifted. Nobody wanted to be the one who broke the sacred flowchart, right?

Flowchart Freddy:

You’ve got it, Primus. And ironically, that “one best way” mentality ended up slowing everyone down.

Spark:

So, Freddy, how exactly did we get into this “one best way” mindset in the first place?

Flowchart Freddy:

It goes way back to Tayloristic principles, where managers do the thinking and workers do the doing. The assumption was that if experts at the top designed efficient routines, the rest should just follow these routines and their orders. It worked in a stable assembly-line world: each person repeated a single task with minimal variation. Over time, that turned into massive bureaucracies of “process managers” who tried to keep these big value chains effective and efficient.

Primus:

But as organizations grew more complex, that top-down design became harder to manage, right?

Flowchart Freddy:

Yes. We ended up with monolithic flowcharts, each connecting entire departments – like marketing passing leads to sales, sales to manufacturing, manufacturing to finance. Whenever something changed, you had to modify the entire chain. It was slow and risky, and everyone was scared to break the fragile system.

Coordina:

I see where you’re coming from, Freddy. But that approach also created a heavy separation of competencies. You had management doing “process design” in isolation, and frontline workers simply executing steps. The moment an unforeseen situation arose, nobody on the ground felt empowered to adapt.

Flowchart Freddy:

Well, we believed that standardization was the only way to guarantee consistency. If every department used the same procedures, we thought we’d minimize errors and drive down costs. But it became… unwieldy.

Spark:

So you ended up with these huge, slow-moving hierarchies of process management, all trying to optimize their piece of the puzzle without “endangering” the overall flow?

Flowchart Freddy:

Um, yes. We’d do tiny improvements for our part – like shaving two seconds off an approval – but not if it risked throwing other teams into confusion. And because everything was so interlinked, even a minor tweak required sign-offs from half the company. Meanwhile, the market would shift faster than we could respond.

Coordina:

It sounds like the real issue was that your flowcharts were a static representation of how you hoped operations would work, rather than a dynamic reflection of how work actually happened. Didn’t that hamper your attempts at real efficiency?

Flowchart Freddy:

You’ve hit the nail on the head. We’d cling to these diagrams, expecting folks to follow them to the letter. But in the real world, people improvised. They found shortcuts, made ad hoc changes, or just ignored steps. We called it “process deviation” and tried to clamp down on it – ironically ignoring the fact that these workarounds were often more efficient or necessary for exceptions.

Primus:

So the very complexity of these big, rigid processes meant they were perpetually out of date. The more you tried to keep them “perfect,” the more fragile and disconnected from reality they became.

Flowchart Freddy:

Oh, yeah. I can’t count how many times I revised a master swimlane diagram, only to have a new product launch render it obsolete. But I was stuck in that system – pushing incremental updates, terrified of causing chaos if I changed too much.

Spark:

Sounds like a classic case of local optimization overshadowing global adaptability. But we know from our last few episodes that things eventually shifted. Could you both outline how organizations moved beyond these slow, hierarchical process models to something more… antifragile?

Coordina:

That’s where modular processes, dynamic process architecture, and frontline empowerment come in. But let’s start with how we rethought the “single best way” dogma …

Primus:

Yes please, Coordina. How did organizations break out of that monolithic trap and Tayloristic dogma?

Coordina:

Good question, Primus. Let’s address one critical shift: reconnecting thinking and doing. In the old model, managers designed processes, and workers simply followed them. That separation created a gap where frontline people knew the real problems but had no authority to change anything.

Flowchart Freddy:

That’s precisely what I witnessed. In my era, “process management” was an entire layer of specialists who tried to optimize flows from a distance – like puppet masters. But they rarely listened to day-to-day challenges on the shop floor. They were kept separate to preserve “focus.” It backfired whenever the real world didn’t match the theory.

Primus:

So how did organizations break free of that dogma? Because old-school process managers must’ve resisted giving up their centralized design power.

Coordina:

They had to see that frontline insight is indispensable. Agile process management emerged as a solution. Instead of top-down rollouts of “perfect” processes, you have short cycles where teams propose, test, and refine their own workflows, guided by shared principles. That’s how you merge thinking and doing – the people who execute also shape the processes.

Spark:

So it’s the difference between telling folks to color within the lines vs. letting them draw new lines when they see a better path?

Coordina:

Ha, ha, exactly. At first, there was fear of everything descending into fragmentation and chaos – like losing all consistency in handovers between departments. But antifragile organizations soon realized that if you give teams a framework for agility – like how to do safe experiments, how to share what they learn – you don’t end up with anarchy. You end up with continuous improvement at the edges.

Spark:

So we’re not talking about letting everyone freestyle processes with zero oversight, right? There’s still some overarching structure ensuring teams don’t step on each other’s toes?

Coordina:

And that’s the crucial mindset shift: process management isn’t about enforcing static “best practices,” but about enabling local teams to adapt quickly without endangering the broader system. Antifragile organizations do that by providing clarity on process purpose, interfaces and their actual usage, and constraints – not by prescribing every step.

Primus:

So an agile process organization fosters a dialogue between those who do the work and those who support the work, bridging that manager-worker divide?

Coordina:

Yes, and to be honest, it was a huge relief. It became clear that the frontline had brilliant ideas. Process manager roles shifted from “controller of the flowchart” to “facilitator of better ways.” They began connecting thinking and doing in real time. No more waiting six months for a process reengineering project that might already be outdated by the time it deployed.

Spark:

I assume the digital backbone helped, right? We discussed its influence in Episode 3. Real-time communication and coordination, shared data flows, quick feedback loops?

Coordina:

Absolutely. Once teams can see each other’s workflows, tasks, and timelines, they can self-synchronize. That’s how you maintain reliability and adaptability. You don’t lose standardization entirely; you keep enough structure to ensure alignment, but empower local decision-making. That’s how you break out of the old dogma and keep building on fresh insights.

Primus:

Fantastic. So bridging that gap – allowing those who do the work to also shape how it’s done – unlocked agility. Shall we now explore how that led to modular process libraries and adaptive workflows?

Flowchart Freddy:

Yes, please. I’m eager to see how my beloved flowcharts evolved into something more… alive.

Coordina:

Ok, then let’s jump right in.

Coordina:

Antifragile organizations discovered modular process libraries. Instead of one massive “best practice,” you create a set of building blocks that are highly connective – think of them like LEGO pieces. Each piece handles a specific sub-process, with well-defined interfaces (APIs) that let teams mix and match sub-processes in their own process chain as needed.

Spark:

Do you have an example for that?

Coordina:

Yes, gladly: In purchasing, for instance, you might have established process blocks for your legacy product lines AND also brand-new blocks for your latest digital service innovations.

Flowchart Freddy:

Back in my day, we had one monolithic “procurement flow.” We’d funnel every purchase request – whether it was a common item or something brand new – into the same labyrinth of approvals, cost analysis, supplier checks, and so on. It could take forever, and we’d risk missing out on fast-developing opportunities.

Coordina:

With a modular library, you’d have different “purchase block” options, that you’d tailor to different contexts. One block handles standard items – like basic spare parts for established products – using a streamlined, cost-optimized path. Meanwhile, a separate block manages new, experimental materials for your latest product ideas, focusing on speed, quick validation, maybe even partial funding from an innovation budget.

Flowchart Freddy:

So I wouldn’t have to… foresee every possible operational scenario… and prepare the standardized procurement workflow in advance, thereby engineering it into one slow, bureaucratic nightmare?

Coordina:

You got it, Freddy. Each purchasing flow is a block in the library, with well-defined interfaces. One block ensures rigorous price negotiation and compliance for bulk items; another is designed for rapid supplier onboarding and prototype testing. Teams choose the module that fits their situation and maturity, then integrate it seamlessly with the larger supply chain process.

Spark:

That’s such a shift. It’s like… back then, every company was handed a hammer and told every problem was a nail. But sometimes, you need a wrench. Or duct tape. Or maybe just to ask what the actual problem is before swinging anything at it.

Primus:

Exactly. Modular libraries give teams a deep toolbox to choose from.

Coordina:

Like I use to say: We have options. Always.

Spark:

That sure is helpful not only in operations, but also at the strategic level, right?

Coordina:

Of course. You can pivot much faster, enter territory you formerly had no clue how to get there.

Primus:

So if you shift from stable, high-volume production to some cutting-edge digital data business, you don’t have to stick to the slow supporting processes once made for direct raw material procurement?

Coordina:

Precisely. You’d just select or develop a new purchasing module optimized for agile sourcing of novel parts. Everyone else in the organization sticks to whatever works for them. It’s a prime example of how you adapt operations without overhauling every single workflow.

Flowchart Freddy:

Sounds radical. In my day, I’d fear chaos from too many variations. I wouldn’t have the resources to handle all of them.

Coordina:

It’s not chaotic if you have transparency. The digital backbone ensures everyone sees what modules exist, how they connect, and which ones are in use. If you want to add or tweak a module, it’s documented, tested, and seamlessly integrated. No more waiting on a universal process redesign.

Spark:

But still Coordina, all that transparency wouldn’t have helped Freddy if he simply lacked the resources to handle all the variations that resulted from this system.

Flowchart Freddy:

That’s right, most of the time it was only me and a handful of other process professionals, that would have to take care of all the process interfaces and ensuring consistency in operations.

Coordina:

That’s a fair point. Early on, many organizations relied on a small team – like Freddy and a few colleagues – to manage every interface. It was overwhelming. But as these companies evolved, they started distributing that responsibility to local teams. Each module’s “owners” would maintain and improve their own process blocks.

Flowchart Freddy:

So instead of just me trying to keep track of a thousand variations, many more people would help maintain consistency and effectiveness?

Coordina:

Yes. The central process pros still exist – they ensure global consistency, set standards for interfaces, and provide a catalog of best-practice building blocks. But the day-to-day tweaking, testing, and local optimization happens at the edge.

In essence, each team that isn’t happy with existing solutions in the process library can add a better one, taking advantage of the existing interfaces to integrate their new solution into the library. They then become the owner of that particular solution, with the authority to refine or replace it, as long as they respect the broader system’s interface rules, and coordinate their additions and changes with other users of the library.

Primus:

So it’s a two-tier approach: a lean central group that owns and coordinates the overall architecture, looking for synergetic standardization potential, and distributed teams that own and maintain their specific variations for real-world scenarios, right?

Coordina:

Yes. Think of it like an app store model: the central “store” sets guidelines – security, data formats, naming conventions – but each “app” (process block) is built and maintained by people who actually use it. That way, no single group is drowning in a sea of demands.

Spark:

So, Freddy, that means you can finally pass the torch on everyday improvements to the folks who feel the pain – and see the opportunities – directly!

Flowchart Freddy:

I’ll admit, that’s a huge load off. If I’d had to manage every interface alone, it would’ve been an endless slog. Distributing process ownership means, ironically, I can do a better job focusing on system-wide coherence rather than firefighting every single improvement request.

Primus:

So we solve the resource constraint by decentralizing process ownership while maintaining a shared architectural framework. That’s quite a departure from the old days of one giant “process office” controlling every detail, and outsourcing many operational competencies to external consultancies.

Flowchart Freddy:

Or from the total opposite: Radically decentralized local process fiefdoms, which then severely limited cooperation possibilities across the organization. Each of these fiefdoms more or less worked, if left alone. But if they were suddenly forced to work together, the fun ended. Political games and managerial backstabbing did not help establish cross-department cooperation efforts. Everyone stayed in their silos, no synergies.

Spark:

And with that, maybe we can explore how the two-tier model of agile process management works in real-life scenarios? I mean, how does it function when multiple variants of a process exist at the same time?

Coordina:

Yes! Let’s move into operational diversity and redundancy, which, in many old systems, was considered a form of inefficiency. The new thinking is that variety can be a serious strength, especially when you need to adapt quickly.

Flowchart Freddy:

So you mean intentionally allowing different teams to solve the same problem in different ways? Doesn’t that create duplication of effort – and work against standardization?

Coordina:

Not if it’s appropriately managed. If you have two versions of a workflow – say one for bulk, stable production and another for highly variable, innovative work – then you’re covering more scenarios. Yes, there’s some overlap in design effort, but you gain resilience. If the market shifts or a particular approach fails, you have other options in place.

Primus:

So it’s like having a fallback plan within your operational system?

Coordina:

Right. In antifragile circles, we say, “Redundancy isn’t waste – it’s insurance for innovation.” You keep multiple methods for key processes. Over time, teams refine whichever approach works best in their context. You might end up with three or four variations across different product lines – and that’s okay, as long as the shared architecture keeps them interoperable.

Flowchart Freddy:

It’s a big departure from my old “one best way” worldview. But I can see the appeal. We had so many crises where everything fell apart because we had no alternative. If we’d had a second or third process ready to go – like a backup supply chain route – maybe we’d have recovered faster.

Spark:

Imagine if every airplane had only one engine, just for cost efficiency. Great – until that engine fails.

Coordina:

Haha, yes. So you pay a bit more upfront to maintain multiple engines – err, processes. But you gain a huge advantage if conditions change or something breaks in your main workflow.

Primus:

So how do you stop variety from becoming a total mess? If each team can pick from multiple workflows, how do we ensure they remain interoperable?

Coordina:

Transparency and interface rules. Every version of a workflow must adhere to certain data formats, role definitions, and reporting standards – so the rest of the company can plug into it. That’s how you can run parallel solutions without them clashing. And again, local “owners” maintain their chosen approach, so you don’t have a central bottleneck.

Flowchart Freddy:

So the big revelation is that diversity of operations isn’t a glitch, but a deliberate design choice to make organizations more adaptable. Teams might keep an older but stable approach for core tasks, while others try a new, more promising approach to their context. If the new approach flops, the old one’s still around – no meltdown.

Spark:

Sounds convincing. And that synergy of variety, plus the digital backbone for visibility, plus the modular libraries for easy plugging in and out – that’s how you get flexible operations that can handle big shifts without mass confusion.

Primus:

Well, that covers a lot of ground: from the old “one best way” trap to agile process libraries, operational diversity, and the power of redundancy. Turns out, having multiple workflows isn’t chaos – it’s insurance for innovation.

Spark:

Who’d have guessed that letting a thousand process variations bloom could be healthier than dictating one universal “correct” method? The irony is, all that so-called inefficiency ends up fueling adaptability.

Coordina:

Precisely. We’ve seen how a combination of transparency, empowered ownership, and modular operations keeps everything aligned, even when half the company pursues different opportunities. It’s not about anarchy – it’s about freedom within a framework.

Flowchart Freddy:

And I have to admit, it’s refreshing. My old flowcharts might’ve felt safe, but they were a pain to update. This new approach is more like a dynamic ecosystem – always evolving, but never spiraling out of control, thanks to a shared architecture.

Primus:

Indeed. In the old world, rigid processes became cages. In antifragile systems, they’ve become springboards to rapid innovation. And speaking of structure with freedom, our next episode will dive into governance – how to maintain accountability, transparency, and strategic coherence when everything’s so fluid.

Spark:

That’s right, because even an adaptive organization needs guardrails. Tune in next time to hear how governance works in antifragile environments – and what it means to manage responsibly when power is so decentralized.

Primus:

This has been Futureproof.

Spark:

The concepts presented in this show are the result of years of research, reflection, and experimentation.

Primus:

We bring this content to you free of charge, and free of sponsoring – because we believe these ideas matter.

Spark:

If you enjoyed the episode, please give it a good rating, leave a comment, or share it with someone who’s still stuck in spreadsheet-era thinking.

Primus:

And if you’d like to dive deeper, consider reading the book „The Antifragile Organization: From Hierarchies to Ecosystems“ by Janka Krings-Klebe and Jörg Schreiner. It’s a treasure trove of insights.

Primus:

Thank you for listening – and remember: the future is yours to shape.

Shorts

Have you ever seen a process that looked brilliant on paper but became a drag the moment conditions changed?

Legacy process design worshipped efficiency. But efficiency assumes stability. Antifragile organizations design for movement: short cycles, empowered teams, operations designed for instant adaptation.

Have you watched colleagues tiptoe around a process, reluctant to change it even when it clearly slowed everything down?

Fragile organizations idolize “the one best way of doing things.” Antifragile ones treat processes as living knowledge repositories. They keep experimenting and learning rapidly, knowing that agility beats rigidity every time.

How often have you seen frontline teams know the real problems – but have zero authority to fix them?

Legacy systems split process owners (managers) from process users (workers), and install a tiny “process office” firefighting endless improvement requests. Antifragile systems close the gap: the people doing the work also own and improve the processes. Central experts don’t control every detail – they orchestrate coherence while local teams adapt fast.

What if your organization could swap workflows as easily as snapping in a new LEGO block?

Instead of one giant standardized process, antifragile organizations build modular process libraries. Teams mix and match blocks that fit their context – fast for innovation, rigorous for scale – all connected through shared interfaces. The result: speed without chaos.

Do you treat having multiple options as waste – or as backup engines?

Fragile systems cut “redundancy” in the name of efficiency, leaving no fallback when disruptions hit. Antifragile systems embrace operational diversity: multiple workflows for the same challenge. If one fails in certain contexts, another is ready. Optionality is not waste – it’s insurance when reality detours from your plans.